This article is

courtesy of EY

Author: Ray Beeman

A Biden presidency and Democratic Senate could bring change

to the course of tax policy.

In brief

- The 2020 presidential election season has been

anything but typical. - Mainstay election issues are being viewed

through a crisis lens: reopening the economy is at odds with curbing viral

spread, creating economic uncertainty. - A Biden victory and Democratic control of the

Senate may mean a focus on tax issues to stimulate the economy, perhaps through

increased investments and R&D.

The 2020 presidential election season has been anything but

typical with the unprecedented circumstances of the coronavirus pandemic and a

focus on racial injustice. Mainstay election issues of the economy and health

care are viewed through the lens of crisis: reopening the economy is at odds

with curbing the spread of the virus, and that tension has created economic

uncertainty that the nation is not likely to completely get beyond for some

time. How tax and economic policy will be addressed if Democrats are in control

in 2021 is gaining attention.

The dawn of the pandemic capped a primary season that saw

Democratic candidates draw from a wide menu of tax policy ideas, from

unrealized Obama-era proposals to newer plans like wealth taxes. Presumptive

Democratic nominee Joe Biden had a relatively modest tax platform and has

gotten ahead while hanging back. Most of his economic proposals were presented

as revenue sources for climate, health and education plans last year. While he

has not released a single campaign tax plan, what has been put forward largely

harkens back to the Obama-era, pre-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) playbook: tax

increase proposals from a time when deficits from the previous recession were

the subject of fierce partisan battles.

Making wealthy individuals and corporations “pay their fair

share” has long been a touchstone for Democrats. Mindfulness of where the

economy is in early 2021, however, may temper calls for tax increases in the

near term. Leaders like Senate Finance Committee ranking member Ron Wyden

(D-OR) have said if they have new power in the presidency and/or Senate

majority in 2021, they will first act to repair economic damage before

increasing taxes for the sake of fairness.

Similarly, if the economy is ailing, raising taxes for

deficit reduction may take a back seat given that deficit concerns have largely

been pushed aside in responding to the crisis. Likewise, if President Trump

wins reelection and Republicans still control the Senate, any focus on tax is

likely to be refining and/or making permanent TCJA provisions, not addressing

deficits.

A Biden victory could bring control of the Senate along with

it. An early focus on tax would likely be on stimulating the economy, perhaps

through investments in manufacturing, supply chains, infrastructure and clean

energy, as well as via R&D for technologies like electric vehicles, 5G and

artificial intelligence. Democrats could also seek to bolster public safety net

programs − Biden recently announced a plan on childcare and similar needs — and

address outstanding health care priorities, as well as enact any coronavirus

response measures not agreed to in 2020. These plans could be proposed along

with tax increases, likely rolling back parts of the TCJA and ending the lower

capital gains rate, though some may be deemed stimulus and not paid for.

A Senate Democratic majority probably would be narrow, and

Democrats would likely need to turn to the budget reconciliation process that

allows certain legislation to pass with 51 votes, rather than the 60-vote

filibuster threshold, for a major economic bill that doesn’t have broad

bipartisan support. (That is, unless a new Senate Democratic majority seeks to

change Senate rules regarding the filibuster.) Even with that procedural

advantage, getting to 51 votes could be difficult given splits in ideology

among moderate and progressive Democrats that will play a large role as the

party tries to move on legislation.

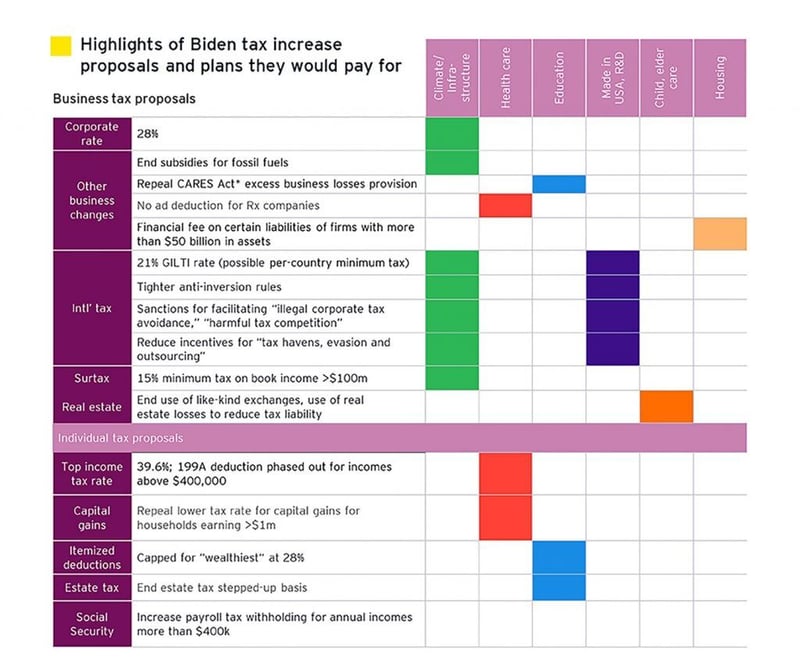

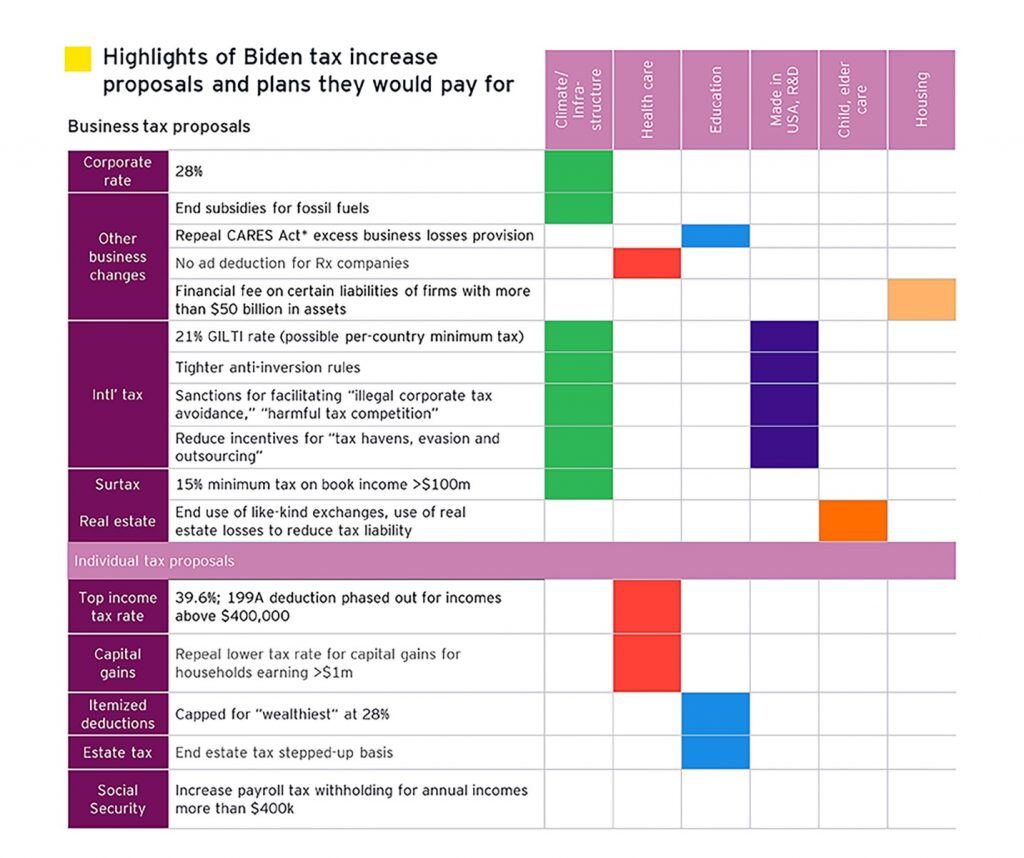

Shaded blocks show how revenue from the various proposals

would be spent.

Business Tax

The 28% corporate rate proposed by Biden was targeted by the

Obama administration when it discussed doing tax reform in 2015 and 2016,

though it was never formally proposed in an Obama Administration budget. Some

more progressive Democrats, including several who ran in the Democratic

presidential primaries, have proposed raising the corporate rate all the way

back to 35%. However, it seems as if the political ceiling is 28%. Along with

raising the corporate rate, Biden has called for a “minimum corporate tax” of

15% applying to book income for companies with net income greater than $100

million.

In the international context, Biden has joined many other

Congressional Democrats in calling for changes to the global intangible

low-taxed income (GILTI) rules, believing it does not have enough teeth to

prevent US companies from taking undue advantage of other international tax

changes included in the TCJA that partially eliminated US tax on foreign-source

earnings.

Biden has proposed combining the 28% corporate tax rate with

a 21% tax rate on GILTI, so he seems to concede that GILTI should be taxed at a

rate lower than the corporate tax rate, but other Democrats have proposed

taxing GILTI at the full US corporate tax rate. Importantly, Biden would go a

step further, joining some other Democrats in proposing to apply GILTI on a

jurisdictional basis, rather than an aggregate basis as it currently applies.

Democrats supporting such a move will find good company with the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development’s efforts to develop model minimum

tax legislation under Pillar 2 of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting 2.0

project that also appears likely to include a per jurisdiction approach. All

these ideas seemed to be aligned with Democrats’ stated desire to remove

incentives for companies to shift US jobs and physical operations overseas.

As part of a housing plan, Biden proposed a financial fee on

certain liabilities of firms with more than $50 billion in assets. No further

details were provided, but it appears the proposal would be modeled after the

Financial Crisis Responsibility Fee proposed by President Obama.

Regarding real estate investment, Biden proposed to pay for

childcare improvements by ending the use of like-kind exchanges and use of real

estate losses to reduce tax liability. Addressing 1031 exchanges is among the

alternatives to a wealth tax put forward by other Democrats, and Biden appears

poised to go the base-broadening, loophole-closing route.

Individual

Individual tax proposals were some of the first put forward

when the campaign kicked off in April 2019. “Let’s get rid of capital gains

loopholes for multimillionaires,” Biden said, adding that capital gains

treatment was behind an Obama-era quote from Warren Buffett that he should not

pay a lower tax rate than his secretary. The lower rate for dividends would

also be repealed, according to campaign officials.

Biden has stated that tax increases won’t affect families

earning less than $400,000 annually. He has also reportedly proposed phasing

out above that dollar limit the Section 199A qualified business income

deduction available to individuals, including many owners of sole

proprietorships, partnerships and S corporations.

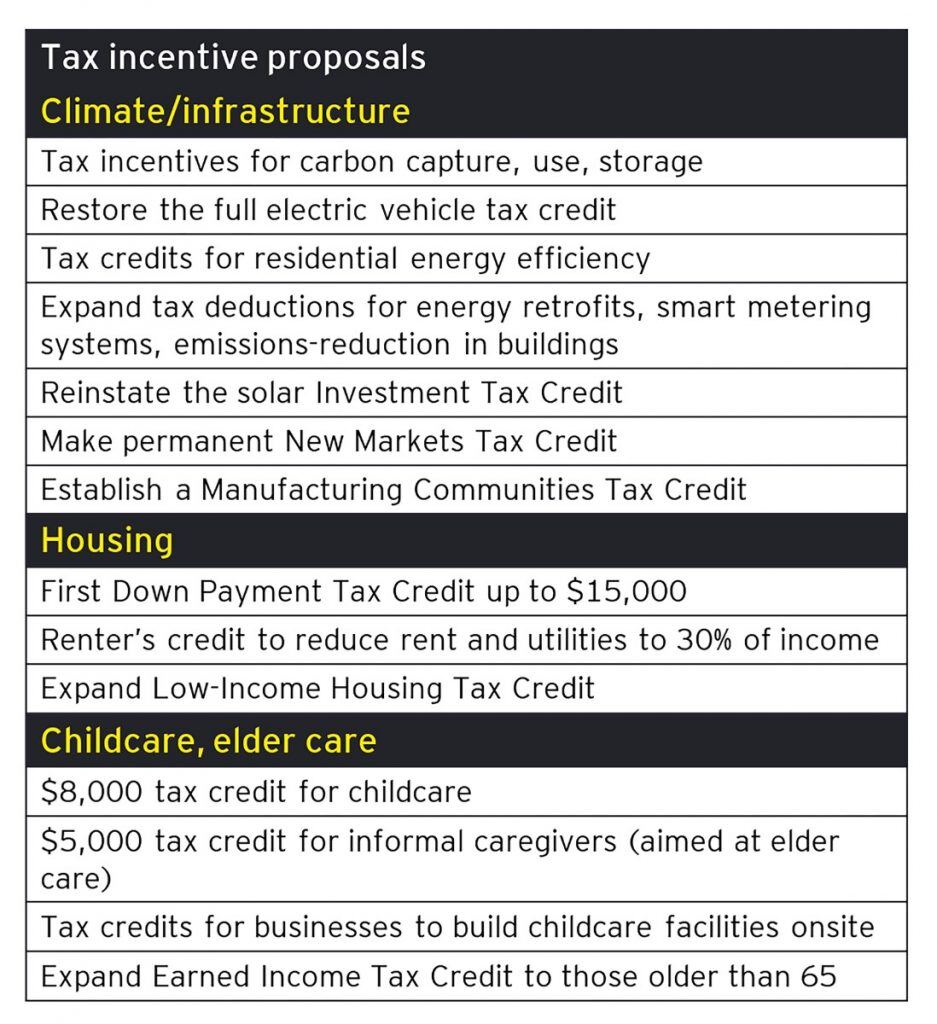

Not all of Biden’s proposals are tax increases. He has also,

in some of the same plans that call for tax provisions as revenue offsets,

proposed to extend, revive or create tax incentives.

Revenue

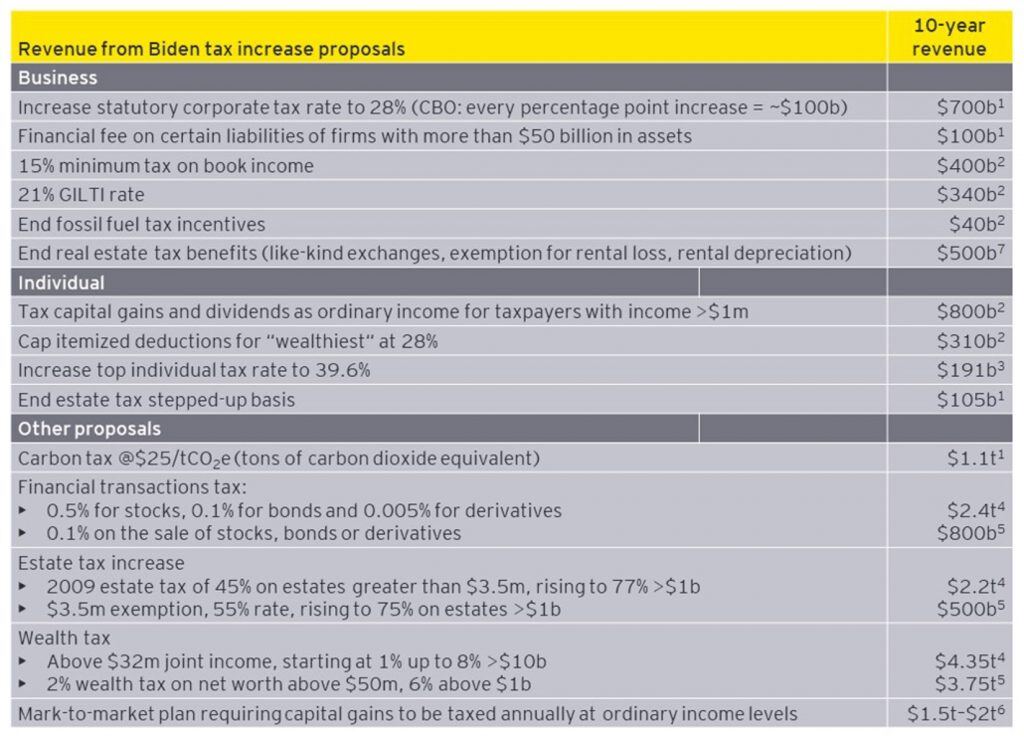

The revenue impact of the Biden campaign’s proposals have

only been scored by nongovernmental think tanks, which have tallied them at or

near $4 trillion in tax increases: $3.8t by both the American Enterprise

Institute (AEI) and Tax Foundation, and $4t by the Tax Policy Center (TPC).

TPC analysis

The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center said about half of that

revenue gain would come from higher taxes on high-income households and about

half would come from higher taxes on businesses, especially corporations. In

the TPC’s breakdown, Biden’s proposal to increase the corporate tax rate to 28%

accounts for about one-third of the additional revenue over 10 years, while

applying Social Security taxes to earnings above $400,000 accounts for about

25%. Increased taxes on capital gains and dividends accounts for another 11%,

and repealing the TCJA’s tax cuts for taxpayers with incomes above $400,000

raises a similar amount (11%). Biden would spend more than $270b of that

revenue on tax credits and income exclusions for family caregiving, retirement

saving, student loan forgiveness, energy efficiency, renewable energy and

expanding the electric vehicle fleet.

Distributionally, TPC said Biden’s plan would raise taxes on

households with income of more than $837,000 (i.e., the top 1%) by an average

of about $299,000, or 17.0% of after-tax income. By contrast, TPC said

taxpayers in the middle-income quintile would see an average tax increase of

$260.

AEI

The conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute’s

analysis of Biden’s tax proposals found that altogether, his policies

would raise about $3.8t over 10 years, slightly lower than the TPC analysis.

AEI estimated that Biden’s most significant tax increases would fall on the top

1% of earners and “overall … make the US tax code more progressive.”

Like TPC, AEI found that the highest-income filers would

produce most of the new revenue, projecting that 72% of new tax revenue in 2021

would come from the top 1% of tax filers, whose after-tax income would fall by

17.8%, with an average tax increase of $118,674. AEI said nearly all the income

and payroll tax increases in Biden’s proposals target the top 1%; tax increases

for the bottom 99% are largely due to business tax hikes.

The conservative Tax Foundation said the Biden tax plan

would reduce GDP by 1.51% over the long term. The group said the plan would

shrink the capital stock by 3.23% and reduce the overall wage rate by 0.98%,

leading to 585,000 fewer full-time equivalent jobs. The group found that on a

dynamic basis, the plan would raise about 15% less revenue than on a

conventional basis over the next decade. Dynamic revenue gains would total

approximately $3.2 trillion between 2021 and 2030 because the relatively

smaller economy would shrink the tax base for payroll, individual income and

business income taxes.

On macroeconomic effects, AEI forecasts that Biden’s tax

policies would reduce the level of US gross domestic product (GDP) relative to

the baseline by 0.06% from 2021 to 2030 by reducing labor supply and capital stock.

AEI estimated that higher effective tax rates on high-income households and

corporations would cause a short-run reduction in GDP, followed by a medium-run

increase due to the reduction in debt.

Other Democratic proposals

The Biden plan has thus far left out some of the more

progressive tax revenue proposals that emerged during the primary campaign

season, including a wealth tax. But many members of Congress will also have

ideas beyond, and to the left, of what he has proposed.

A financial transactions tax has had support in Congress and

was picked up by other candidates. Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) and Rep. Peter

DeFazio (D-OR) sponsored the Wall Street Tax Act of 2019 (S. 647, H.R. 1516) to

impose a 0.1% a tax on securities transactions. Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-VT)

bill (S. 1587), cosponsored by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) would impose a

financial transactions tax of 0.5% for stocks, 0.1% for bonds and 0.005% for

derivatives.

Senator Wyden, who would likely become chairman of the

tax-writing Finance Committee should Democrats take control of the Senate, has

proposed a plan to impose a mark-to-market approach requiring capital

gains to be taxed annually at ordinary income levels.

“Anti-deferral [mark-to-market] accounting rules” would only

apply to individuals with more than $1m in annual income or $10m in assets.

Applicable taxpayers would be required to pay annual taxes on unrealized gains

and take a deduction for unrealized losses on liquid assets, such as stock,

while for illiquid assets mark-to-market would not apply but a look-back charge

would be imposed on gains realized upon the sale of these assets.

Biden hasn’t proposed estate tax changes beyond eliminating

stepped-up basis, but Biden-Sanders “unity” principles released in July said

they should be “raised back to the historical norm.” Democrats have at times

urged a return to the 2009 regime: $3.5m exemption and 45% rate. Interest

remains in repealing the $10,000 state and local tax deduction cap.

The

economy in 2021

At the beginning of 2021, it is likely that the focus will

be on reviving the economy while still tending to the demands of the

coronavirus. It is possible more virus-related relief will be needed, or that

Democrats, if in control, would try to enact some of the measures that

President Trump and Senate Republicans have not agreed to in coronavirus

measures. There are several tax items in the House-passed Health and Economic

Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act that are not likely to be agreed to by

Republicans this year, and so could be ripe for action if Democrats control

Washington in 2021:

- Making the child tax credit fully

refundable, increasing the amount to $3,000 per child ($3,600 for a child

under age 6), and making 17-year-olds qualifying children - Making the child and dependent care

tax credit fully refundable and increasing the maximum credit rate to 50% - Increasing the exclusion for dependent care assistance

from $5,000 to $10,500

There will also be a focus on recovery and job creation.

Biden has said that if elected, he would provide “further immediate relief” to

families, small businesses and communities dealing with the coronavirus

pandemic.

In terms of stimulus, Biden has thus far outlined plans to

invest a combined $700b in procurement and R&D designed to boost US

manufacturers and stimulate the economy, as well as $2t in clean energy and

infrastructure investment. In both cases, Biden has emphasized the job-creation

benefits of the plans and the campaign has signaled they would be partially

paid for by reversing tax cuts for corporations and impose “common-sense tax

reforms that finally make sure the wealthiest Americans pay their fair share.”

Probably the best model for a united government coming into power amid a crisis

was President Obama working largely with the Democratic Congress on financial

rescue and recovery in 2009. The new president had campaign tax proposals, but

those largely were jettisoned initially to focus on recovery.

If racial economic equality is an early priority, Biden has

proposed opportunity zone changes in a context that focuses on creating jobs

for low-income residents and otherwise providing a direct financial impact to

households, as well as additional review of and reporting by opportunity zone

recipients.

He

also proposed making permanent the New Markets Tax Credit.

At some point, however, tax increases will likely be

proposed for what is already a massive revenue hole from the coronavirus. The

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) on April 24 said the FY2020 budget

deficit is projected to be $3.7t. The deficit was $864b just for June.

Also inevitable: a discussion over the future of Social Security, with the

troubling outlook for the program over at least the past two decades now even

worse with an aging population and the payroll and other economic effects of

the pandemic, which some say accelerates the insolvency date by about a year.

Biden proposes to impose Social Security payroll taxes on incomes greater than

$400,000 per year, in addition to the first $137,000 in annual income, with no

additional tax on income in the doughnut hole in between.

Principles

behind Democratic tax policy

The “fair share” principle goes back to the Obama

administration and has continued in the wake of the TCJA, which Democrats

say tilted benefits toward corporations and wealthy individuals. While

Democrats are seen as having won the 2018 congressional elections largely on

the issue of health care, they were also highly critical of the TCJA.

Now-Speaker Pelosi criticized the tax bill for adding to the deficit, saying

lawmakers should “make the middle-class tax cuts permanent” but “bring balance”

to the tax system and reduce debt “by having a revenue package that does just

that, that puts the middle class first.” She also suggested the 21% corporate

income tax rate is too low. Democrats are likely to stick to these principles.

While Democrats back making permanent most TCJA provisions

for individuals that expire after 2025, it is less clear how they will approach

business changes/phase-outs sooner:

- The 30% limitation on the deduction of

interest expense is calculated without depreciation and amortization after

2021 (i.e., earnings before interest and taxes vs. earnings before

interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) - Bonus depreciation phased down 20%

yearly after 2022 - Amortization of R&D expense

beginning in 2022 - Reduction in the Section 250 deduction for purposes of

GILTI and foreign-derived intangible income rules

Process

If Democrats have a slim Senate majority, which is likely to

be the case if they win control of the chamber, the procedural focus will

likely be on the budget reconciliation process, which has often been used in

unified government situations in which the controlling party lacks 60 Senate

votes. Reconciliation has frequently been used by Congress to make changes to

the tax code and modify mandatory spending programs.

Reconciliation bills can pass the Senate with 51 votes,

though there are strict rules accompanying the use of the process, including

that reconciliation bills cannot contribute to the budget deficit for the

period outside the budget window. Use of the budget reconciliation requires two

steps:

- Both the House and Senate must pass

the same concurrent budget resolution that contains reconciliation

instructions to committees to change spending and/or revenue numbers. The

reconciliation instructions don’t prescribe specific policies to achieve

the number targets. - Bills that adhere to the resolution must then be passed

and signed into law.

Reconciliation is generally easier to do when raising taxes

than cutting taxes since reconciliation originally was designed as a deficit

reduction measure, and there is no worry about 10-year sunsets or fitting the

contents of the bill within a revenue constraint. Of course, reconciliation

becomes essentially irrelevant should Democrats pursue and achieve repeal of

the 60-vote Senate filibuster to their agenda. Not all Democrats support this

move, however, and Biden’s explicit backing would be surprising given his decades

in the Senate. Allies like Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) back the move, but

moderate Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) has dismissed the idea. It did get a boost

from former President Obama July 30.

Lessons from 2017

While fiscal stimulus seems a top contender as an early

agenda item, a first bill under Democratic control may not involve tax policy.

The same was true in 2017; as the Republican majorities took office that

January, they planned to use budget reconciliation to repeal the Affordable

Care Act and secure a win for the new president, quickly passing a budget

resolution for FY 2017 − several months into that fiscal year − with

reconciliation instructions to that effect. But that effort ended in failure in

July as then-Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) joined two other Republicans in narrowly

defeating the bill on the floor. So in August, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell

(R-KY) quickly pivoted to tax reform, and Republicans drafted a second budget

resolution (this one for FY 2018) with new instructions that also produced the

TCJA. The GOP leadership was able to ease the path to passage by omitting a

plan by House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady (R-TX) for a border

adjustment tax.

Then, after an intraparty debate over the size of the

deficit that the tax reform bill would permit, Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA) sealed a

key agreement with then-Budget Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-TN), a

moderate, to allow the new budget resolution to increase the deficit by $1.5t,

promising that increased revenue spurred by economic growth would make up any

projected shortfall. Those and other maneuvers ultimately helped lock in

winning votes in the House and Senate, and President Trump signed the bill on

December 22 − perhaps a land-speed record for a tax reform law. Democrats would

likely have to navigate through similar disagreements between moderates and

liberals to get a reconciliation bill quickly.

Should the 60-vote Senate filibuster remain intact, thereby

requiring the reconciliation process to advance major agenda items, a similar

construct could unfold in 2021: since Congress has not approved a FY 2021

budget resolution, that process could be revisited by Democrats early next

year, creating an initial reconciliation opportunity followed by a second

reconciliation opening in calendar year 2021 with adoption of a FY 2022 budget

resolution.

Timing

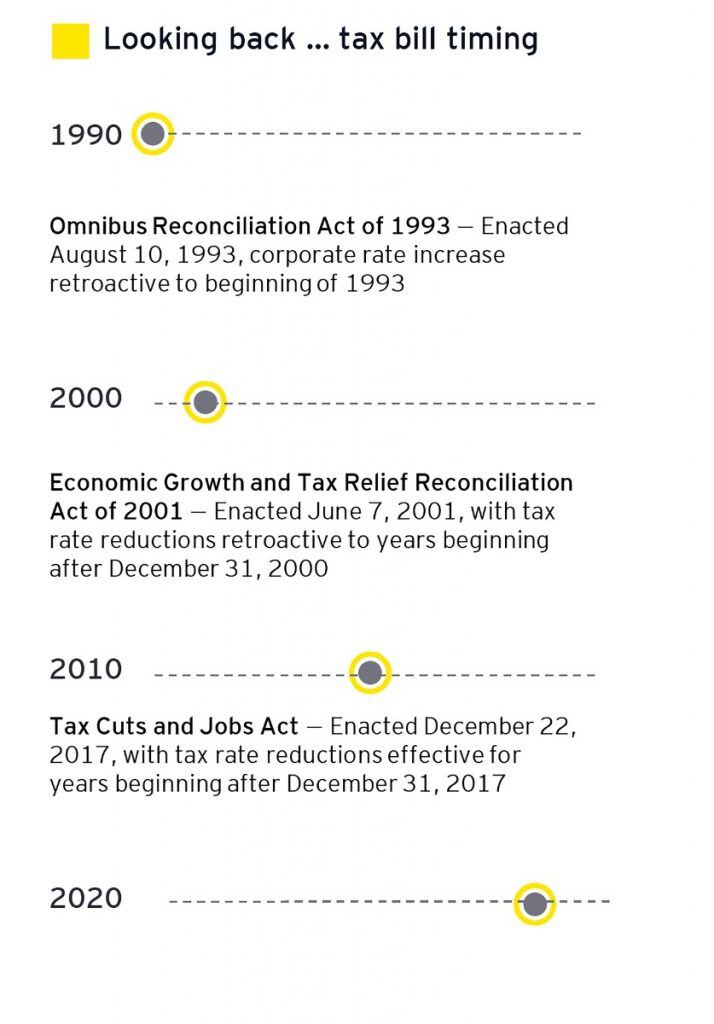

Whatever the shape of a first economic bill, it will likely

take several months to pass. With Republicans in control in 2001, it took until

Memorial Day to get the first Bush tax cut bill (Economic Growth and Tax Relief

Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA)) done. Under GOP control again in 2017, detailed

tax reform proposals came out November and then there was a legislative sprint

until the end of the year. The last previous change to the statutory corporate

income tax rate (an increase) was in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of

1993, which wasn’t enacted until August of that year.

Also of interest is the matter of the effective date,

especially as it relates to potential increases in the corporate rate. The 1993

corporate rate change, the last before the TCJA, took effect retroactively to

January 1, 1993, although it was only a one-point increase. The 2001 Bush tax

cuts (EGTRRA) were retroactive to the beginning of the year. The TCJA was

immediate but not retroactive, and that was a rate cut. The current thinking is

that a significant tax bill would take well into 2021 to complete, with an

effective date of the beginning of 2022.

Conclusion

While exact plans of Democrats, should they control Congress

and the presidency in 2021, will continue to develop in the months ahead, they

will likely depend in part on the state of the economy at that time. A

near-term economic bill could be expected with follow-on legislative efforts

addressing additional Democratic priorities. The early priority is likely to be

COVID-19 recovery and other stimulus. Infrastructure investments will be a

priority, as will proposals related to climate change. Some “low-hanging fruit”

tax provisions could be tapped as an early revenue source and the first shot at

improving tax fairness.

Action could follow later on long-held priorities that are

made more urgent by the virus and its effect on the economy, like shoring up

the social safety net, health care and education. Tax proposals are likely

to eventually be tapped for revenue, in the fashion Biden has taken during the

campaign: eschewing a wealth tax or other new concepts in favor of base

broadening, loophole closing and turning the tax rate dials. Based on Biden’s

comments during the campaign, tax increases that could be turned to for early

revenue include repealing the preferential tax treatment capital gains for

higher-income individuals, ending estate tax stepped-up basis and, perhaps,

long-time Democratic targets like carried interest. These could be the first

steps toward the rebalancing of the tax system to which Democrats aspire, with

a corporate tax rate increase and other more systemic changes perhaps facing a

slightly longer runway for enactment.

Sources

1 CBO, “Options for Reducing the Deficit, 2019 to 2028,”

12/13/18

2 Bloomberg, “Biden to Target Tax-Avoiding Companies

… ,” citing Biden campaign officials, 12/4/19

3 JCX-53-19 (Joint Committee on Taxation score of House

State and Local Tax bill)

4 Sanders campaign

5 Warren campaign

6 Senate Finance Committee ranking member Ron Wyden (D-OR),

September 2019 white paper

7 Tax Policy Center analysis of Biden plan

Summary

While Biden has not released a comprehensive campaign tax

plan, what has been put forward harkens back to the pre-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

(TCJA) playbook: tax increase proposals from a time when deficits from the

previous recession were the subject of fierce partisan battles. If control

shifts Democratic but the economy is still ailing, raising taxes for deficit

reduction may, however, take a back seat. Likewise, if President Trump wins

reelection and Republicans still control the Senate, any focus on tax is likely

to be on refining and/or making permanent TCJA provisions, not addressing

deficits.